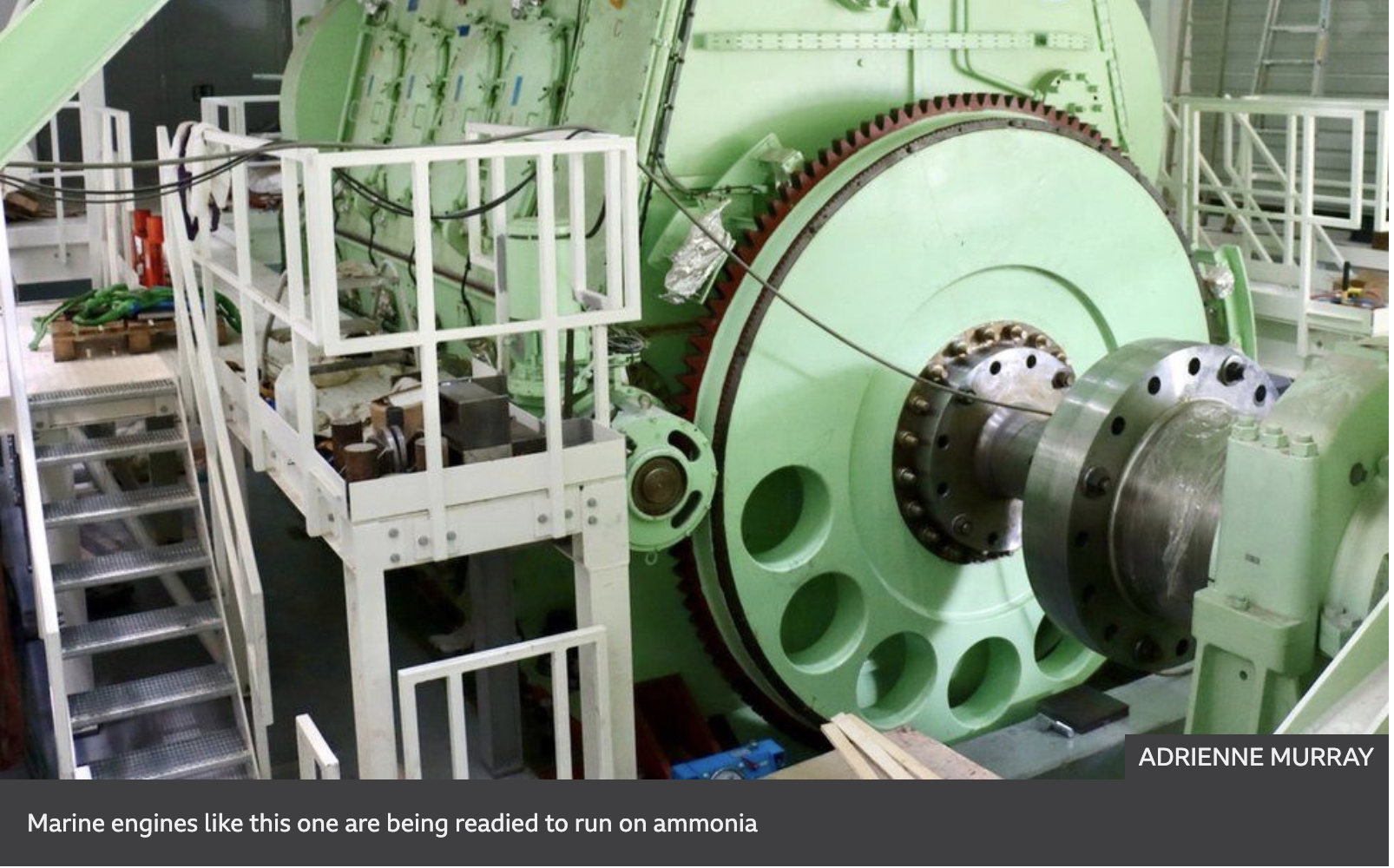

An enormous engine, the height of three floors, growls loudly at a test centre in Copenhagen. Nearby a team of engineers supervise it from a control room resembling a ship’s bridge.

Usually such an engine would be propelling a large ship across the sea, but this one is being prepared to take part in a ground-breaking project.

Engineers want to see if they can make it run on liquid ammonia.

Ammonia has long been a key component in fertiliser, cleaning products and refrigerators.

But in the search for new cleaner fuels, the foul-smelling substance has emerged as a frontrunner to power ocean-going ships.

Around 90% of all goods traded globally are transported by sea. But ships are gas guzzlers. Marine transport produces around 2% of global greenhouse gas emissions.

The International Maritime Organization (IMO) wants to halve emissions by 2050, from 2008 levels. That requires a substantial shift to green technology.

Brian Soerensen, a research and development chief at Man Energy Solutions, says several fuels are being explored: “One of the options we believe will be ammonia. Methanol could be another one, biofuel could be a third.”

Ammonia has an advantage as it contains no carbon, so can burn in an engine without emitting carbon dioxide.

By early 2024, Man Energy Solutions plans to install an ammonia-ready engine on a ship. The first models will be dual-fuel, able to run on traditional marine gas oil as well.

While it is less energy-rich than today’s marine fuels, liquid ammonia is more energy-dense than hydrogen, another zero-emission fuel.

Hydrogen has already powered cars, planes and trains. It’s cheaper to produce than ammonia, but harder to handle as it has to be stored at minus 253C. Ammonia becomes liquid below minus 34C and at higher temperatures if under pressure.

“Ammonia sits very nicely in the middle,” says Dr Tristan Smith, an expert in low carbon shipping from University College London. “It’s not too expensive to store and not too expensive to produce.”

There are challenges. Burning ammonia can create polluting nitrous oxides, therefore the exhaust needs cleaning up. It is also toxic, so requires careful handling and storage.

However, safety know-how and some port infrastructure are already in place, says Mr Soerensen, because the fertiliser industry is well-established.

“It’s being transported seaborne today. We know how to handle ammonia on board a ship, not as a fuel, but as a cargo.”

Meanwhile, Norwegian shipping company Eidesvik plans to install ammonia fuel cells on a vessel by late 2023. Like batteries, these generate electrical energy to power a motor. Project partner Prototech has already begun developing a test version.

The supply ship, Viking Energy, will sail round-trips of 345 miles (555km). The hybrid vessel will also use liquefied natural gas (LNG).

Vermund Hjelland, vice president of technology and development at Eidesvik, says fuel cells are more efficient and cost-effective, for such short, predictable routes. “You can have smaller tanks and get more kilowatt-hours out of the same amount of fuel.

“The picture is different compared to a super-tanker,” he adds. “It very much depends whether weight is an issue.”